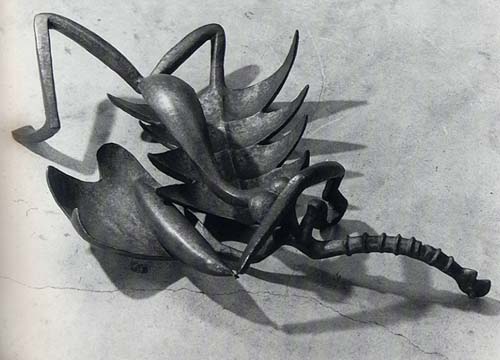

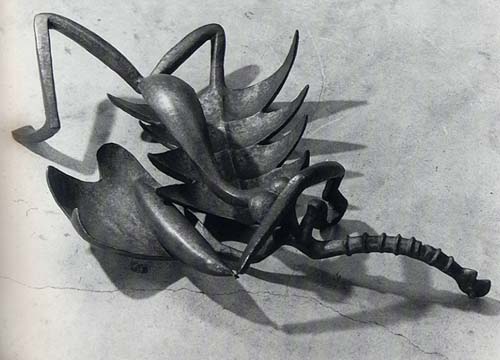

Alberto Giacometti

Woman with Her Throat Cut1932

bronze

8 x 34 1/2 x 25 in.

at MoMA

I know it is possible that some you are hungry for more up-to-date readings. But let's be honest; I don't think we're going to be able to find anything which is more contemporary or daring than what I am teaching you now. Plenty of people are trying to produce "new" art out there; but our culture's insatiable capitalist demand for novelty (a sublimated form of animal hunger) is the source of some of the world's biggest problems. For what it's worth, of far greater critical concern today, and I am reminded of this by things I heard while at AWP in Denver, is not the issue of originality but rather of repetition. But this aside, the critics need time not only to create a new set of concepts, but simply to find these new artists, in addition to continuing their work on more familiar older artists whose work still demands to studied, whose legacies are still very much tied up in the scholarly equivalent of protracted inheritance litigation. Not that there's absolutely no one writing on stuff being produced this very minute. But most of that writing will not appear in journals so much as in 'zines. The more current the art gets, the more the writings on it will take the form of mere reviews and celebrations rather than deeply considered studies. Leo Steinberg, as you will recall, discussed a seven-to-ten-year lag between the moment of production and popular acceptance. I would suggest that the scholar, whose job it is not simply to accept something but also to explain it, lags even farther behind. We shouldn't expect the most preeminent critics of our day to write on hip-hop/cyber/metal/punk/graffiti art. These people, many of them older than your parents, are struggling with their own ideological fathers, their own anxiety of influence. The people we've been reading will simply not get around to fighting your culture wars. If anyone is going to write the articles on "today's" scene which you now want to read, that person will have to be you.

To open up a huge debate in the history of modern art, Hal Foster's critique of Peter Burger's Theory of The Avant-Garde; is that Burger's presentation of art history is far too linear, and far too sure that art movements were what they were in their very moment of their emergence, and further that they were consciously aware of what they were. Burger believes, if you will, that we can take the Avant-Garde at its word. His views cultural expression and critical thought as progressively liberating themselves from tradition by means of decisive encounters with otherness, and as a result coming to a consciousness of their own essence and freedom in practice; is all very much the product of Burger's Hegelian Marxism. Burger's take on the Avant-Garde, which for him represented a historical movement which deliberately set about to emancipate itself from the Art Institution, is entirely informed by his belief (of Frankfurt School, which is to say

Institute for Social Reasearch provenance) that History is linear and progressive, and that to continue to abide in a set of practices once they have been successfully critiqued and historicized is to wallow in fantasy, denial, servitude, decadence. For this reason Burger's considers Neo-Avant-Gardist such as Rauschenberg, Johns, Judd and Nauman, to be infantile and perverse. The

historical avant-garde, for Burger, was indeed bizarre and shocking to the uninitiated, no doubt; but it was simultaneously nothing if not canny about its own intentions and methods; and it was, above all else, truly original.

Now, it is this (comparatively conservative) view of history and critical thought as "decisive" and ultimately meaningful which is precisely what Hal Foster rejects. Instead, he asserts that the so-called 'historical' Avant-Garde was never a moment of newly won freedom, clarity and self-awareness; or originality, simplicity and integrity; within a general dialectical trajectory of cultural Enlightenment. Nor should we percieve the Avant-Garde as a shrewd form of cynical withdrawal from what Adorno called the "culture industry". Rather, the Avant-Garde, for Foster, marks a point of radical "indecision"--of trauma, loss of consciousness, and convulsive identity. The Avant-Garde stands not as a culmination or breakthrough so much as a point of unresolved and irreducible conflict. The avant-garde emerges in a place of total difference, and as such stands as the first of multiple iterations (

click), of which the Neo-Avant-Garde of the 60s was one such repetition. For Foster, the art object is never finished, at least certainly not at the moment the artist applies the so-called

touche finale. Rather, art objects, and most apparently those associated with the avant-garde, powerfully refute this idea. Instead, they are the very stuff of interminable analysis; their final completion is always deferred through an infinite series of interpretations which take the form not only of critical writings on them but also their presentation within museums and the university, as well as their reproduction in mass-media.

Whereas Burger claims that the Avant-Garde was authentically what it was in its unique historical moment, and that all subsequent returns to it are parasitic and servile; Foster insists that the Avant-Garde is that mode of expression which radically challenges our understanding of History in general, which by its intrinsic problematicity has always assumed the possibility of

reiteration to be its most constitutive feature. Though Burger may see the Avant-Garde as a rational and

lisible (i.e., readable)

lexeme (i.e., statement) which finds its full meaning within the general grammar of a grand developmental narrative, Foster demands on the contrary that we see the Avant-Garde rather as a Return of the Real (

click), an irruption of the speaking body within the space of the subject of speech. For Foster, the Avant-Garde is not a significant utterance so much as a hiccup, an stutter, a recurring blockage of the channels of communication. And if this is so, the very success of the historical Avant-Garde for which Burger argues, would in fact constitute it's veritable failure.

At this point it would make perfect sense for us to inaugurate some discussion, any discussion at all, of Adorno and Horkheimer's (as well as Walter Benjamin's) interest in the Avant-Garde and Surrealism, as possible strategies of escape from the all-encompassing system of Capitalist Utilitarianism which they called the Dialectic of Enlightenment (

click). As Michael Weingrad demonstrates at great length in his essay "The College of Sociology and The Institute of Social Research" (

click), the relationship between Bataille's circle and that of Adorno was anything but a harmonious matrimony. Still, if you read Weingrad's piece, it is quite easy to see how much his historicizing method depends upon the very same clear expository style which characterized Peter Burger, who ultimately is entirely intolerant of artist and critical inscrutibility, and the free play of signification in general. (Be sure to click on the image off to the right after reading Burger's unmistakably defensive, and perhaps quaintly pugilistic, opening posture below.)

In the begining was a smile, an irritating smile [or what last night I called a smirk]  , in no way comparable to the masculine activity of the smiling in one's beard with which the scientists in Musil's A Man Without Qualities follow the talk in Diotima's salon. Theirs is the expression of deference and incompetence. In vain, I seek a similarly apropos phrase to define the smile in question here that always appears on the lips of the advocates of poststructuralism when one intends to propose an argument. So arrives the thought that to understand poststructuralism means nothing other than to understand this smile.

, in no way comparable to the masculine activity of the smiling in one's beard with which the scientists in Musil's A Man Without Qualities follow the talk in Diotima's salon. Theirs is the expression of deference and incompetence. In vain, I seek a similarly apropos phrase to define the smile in question here that always appears on the lips of the advocates of poststructuralism when one intends to propose an argument. So arrives the thought that to understand poststructuralism means nothing other than to understand this smile.

But would it not be possible for us read the encounter, and eventual judgment of Frankfurt upon Paris in far more traumatic terms? to read this critical scrutiny and dismissal rather in terms of a far more vexed moment of

meconnaisance (

click), in which the Self and Other exchange places, and discover or cathect (which is to say contract, or catch) the Truth of their identities and beliefs in so far as they lose their former selves in an encounter with radical Otherness? How would highly-sophisticated intellectual German Marxist Jews react upon encountering the most cutting-edge French intellectuals, who claimed to be experimenting critically with radical alternatives to Capitalism, and who claimed to welcome them as friends and protegees into their most intimate (i.e., secret) enclaves; how would Adorno and Benjamin react upon finding Bataille and Caillois toying with Nietzsche and Fascist ideology? Could we expect such a reaction, no matter by whom, ever to be objective? What would it mean to read the various essays, letters and memoirs, and take Adorno and Horkheimer, or Benjamin, at their word?

In reading Michael Weingrad's very circumspectly researched piece of scholarship, can we help but feel that we are reading recollections of recollections, reconstructions of reconstructions, as well as disavowals of disavowals, all of them peppered with countless textual as well as cognitive lacunae, blind spots? Is there not a quasi-libidinal ritualism to this sort of international curiosity and intrigue? Read by the mediating albeit lugubrious candle flame of Kojeve's (in)famous lectures on Hegel (which indeed helped lure the Frankfurt School to Paris), is it really possible to view all cont(r)acts between Bataille and Adorno (the latter being the world's most sophisticated critic of capitalist calculation) as mere rational laissez-faire negotiations, unmotivated by any residual idealist speculations or the equivocations of Desire? Weingrad has done a superb job of organizing and summarizing the source materials currently availible to us. But still it strikes me that far more remains to be done in terms of analyzing this particular station on Critical Theory's itinerary from Germany to America. In other words, we do not simply find a need to review the lessons of the past; but in a much more radical sense, we find ourselves compelled to return to them. We find ourselves unable but to repeat, unable but to begin, once more, again.

Thus, when 'Nazi' brushed against 'surrealist' that night, I wanted to deny such associations, and I doubt I was alone. . . . Clearly the [encounter] violated a critical taboo, and a nervous silence ensued; it was the silence of an interpretive breakdown. I did not think about that silence for several years (such was the strength of my denial) . . .. The [solution to this] question [Foster continues] was how to make [the appropriate] connections and, even more obscure at least to me, why I wanted to do so. The text that follows is thus provisional at best, and I present it only because I can now bear its fractured argument better than I can the restive silence that proceeded it.

Well now, what do you think of the essay below for next time? Is it recent enough, pertinent enough, different enough? Or just another iteration of the same old same old?

as pure differential; or the movement-image, as parastaltic advance ; are here to be understood in terms of mobile devices, or dissevering dispositifs which produce schism (σχισμή) and trauma (τραύμα). They are cutting machines, buzzsaws which literally lacerate and grind their way through the corporeal continuum of the life-world. Thus, as we saw with Hitchcock's elevation of the souveneir postcard to the status of background and frame, here Deleuze gives us an alternative version of how content, or in this case a sub-genre, rises to constitute the set of which it is itself a member. All film making is a form of cutting; all films are slasher films.

as pure differential; or the movement-image, as parastaltic advance ; are here to be understood in terms of mobile devices, or dissevering dispositifs which produce schism (σχισμή) and trauma (τραύμα). They are cutting machines, buzzsaws which literally lacerate and grind their way through the corporeal continuum of the life-world. Thus, as we saw with Hitchcock's elevation of the souveneir postcard to the status of background and frame, here Deleuze gives us an alternative version of how content, or in this case a sub-genre, rises to constitute the set of which it is itself a member. All film making is a form of cutting; all films are slasher films.